A last-ditch effort to block enforcement of a law aimed at Native Americans has failed in court. But the law has also triggered a backlash—and thousands have new credentials.

North Dakota’s Native American communities suffered a setback on Thursday, as a court ruled that the state’s voter suppression law can remain in effect for this year’s election. But outrage over the law has led to a huge backlash and grassroots efforts to help people vote despite the law.

In 2012, now-Sen. Heidi Heitkamp won a surprise, razor-thin victory to become North Dakota’s only statewide elected Democrat. She won by fewer than 3,000 votes. There are roughly 30,000 Native Americans in North Dakota, roughly 5 percent of the state population, and they overwhelmingly supported Heitkamp.

In response, the state’s Republican-dominated legislature passed a new law in that seems specifically intended to make it harder for Native Americans to vote. In addition to a strict ID requirement, the law requires all voters to provide proof of a residential street address—something many Natives who live on reservations simply do not have.

Large numbers of Native Americans use post office boxes to receive mail and live on unmarked and unsigned streets. Many others live with various family members. Still others have no idea that their streets even have names. In total, about 5,000 Native Americans lack the required voter ID—larger than the electoral margin in 2016.

Needless to say, there were no documented instances of voter fraud involving people without street addresses.

“They didn’t need an address when they took our children and rounded them up into boarding schools,” Chase Iron Eyes, a Native American lawyer who lost a congressional bid in 2016, told NBC News. “And they didn’t need an address when they conscripted us to fight in the military and make a worthy and honorable sacrifice. But now they need our address when we want to exercise our right to vote.”

Tribes represented by the Native American Rights Fund sued immediately. In 2016, they won an injunction against the law, but in response to that, the North Dakota Legislative Assembly passed a new version, with substantially similar requirements.

The tribes won again in April of this year, when a district court enjoined enforcement of the new law, but they then lost on appeal, when the Eighth Circuit removed the injunction. Last month, the Supreme Court declined to put it back in place, with Justices Kagan and Ginsburg dissenting.

The tribes’ last-ditch effort was a motion for a new and more limited injunction, which they filed on Oct. 30. But on Nov. 1, that, too, was denied, with the district court writing that it was just too close to next week’s election to change the rules now.

So the North Dakota law will be in effect next week. But Native Americans have a plan to defeat it at the polls.

First, a coalition of groups led by the Lakota People’s Law Project and the national Native American group Four Directions have been furiously helping people get proper IDs free of charge. According to the Associated Press, they’ve helped more than 2,000 people get them.

The New York Times reported that one band of Chippewa printed so many IDs that the machine overheated and started melting the cards.

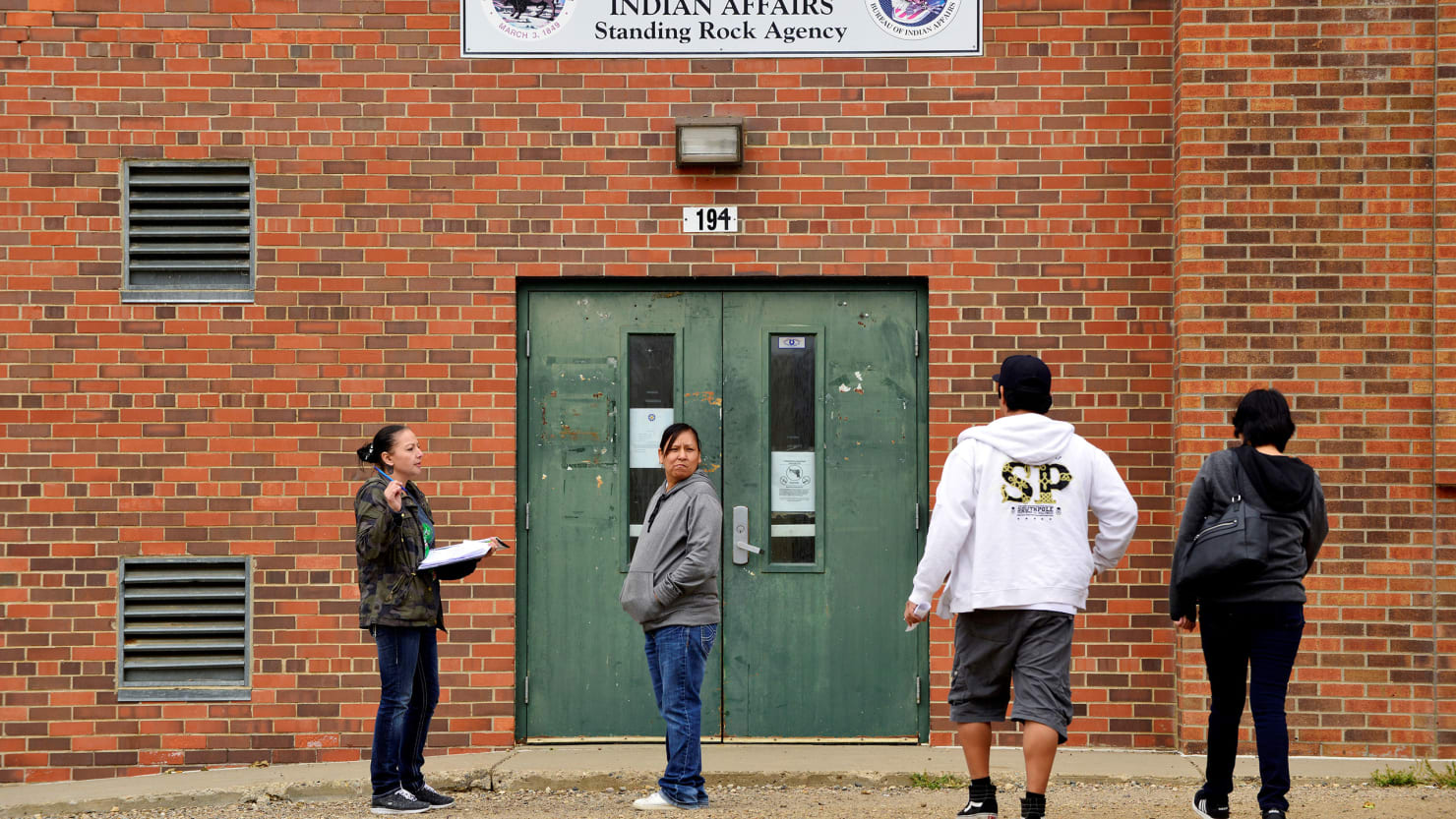

“We’re at our best in crisis,” Phyllis Young, an organizer on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation—made famous in 2016 when thousands of young people took up the cause to stop a pipeline from being built near tribal lands—told the AP. Young said the GOP’s overt voter suppression "is only making us more aware of our rights, more energized, and more likely to vote this November." Young’s own address was, until she had it changed this year, “7 miles by highway marker 14 by the Porcupine turnoff.”

Tribes participating in the effort include the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Spirit Lake Nation, and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

Second, Four Directions is helping tribes create residential addresses where none have existed before. Using satellite imagery, voters can point to the locations of their homes on a map and are assigned unique address identifiers—even on the spot. On Election Day, tribal officials will be stationed at every polling site in every reservation in the state, with tribal letterhead in hand, ready to assign addresses.

“This is democracy at work!” Four Directions tweeted on Oct. 30. “Voter engagement is high. We have DOUBLED Absentee votes at Standing Rock as of 3:47 pm today.”

Celebrities including Mark Ruffalo and Dave Matthews have also gotten involved, with the Stand-N-Vote initiative, which hopes to capitalize on resentment against the voting restrictions, and the national awareness of the Standing Rock Sioux, to enable more Native Americans to vote.

It’s unknown whether these efforts will counterbalance North Dakota’s voter suppression laws, or whether they will make enough of a difference for Heitkamp, who trails her opponent by as much as 12 points. Then again, those polls are based on likely voters. As we all saw in 2016, when blocs of voters show up in more numbers than they have done in the past, they can defy polls. Just ask Sam Wang.

Regardless of the result of this year’s election, North Dakota voter suppression has backfired: Thousands of newly credentialed Native American voters have shifted the electoral math in North Dakota.

And they are angry. Alexis Davis, 19, chairwoman of the Turtle Mountain Youth Council, told the AP, “It’s like, oh you want to make this harder for me? Oh, you want to take away my rights? It’s like, no, now I’m going to fight that, and I’m going to be more resilient, and I’m going to make sure that I’m going to go vote.”

Comments

Post a Comment